October 16, 2023

John Brown was an American Abolitionist born on May 9th,1800. Brown was a well-known figure from his abolitionist fighting in Bleeding Kansas, but truly became famed for his raid and attempted initiation of a slave rebellion in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), in October 1859.

In order to instigate a slave rebellion in the soon-to-be Confederate states, Brown needed lots of weaponry. He wanted to take the United States Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, stealing the weapons and ammunition there and arming slaves as they moved down the Appalachian mountains. Harpers Ferry’s location made it the ideal spot to begin–it directly connected Maryland, the C&O Canal and B&O Railroad, and the Appalachian Mountains.

The National Armory manufactured weapons and ammunition that were sent through the country with these connections, and would become vital to the Confederacy in the future. In Brown’s eyes, seizing the armory would be a great start for the Abolitionists in the imminent war–and an even better place to start for a successful slave rebellion. If he and his men controlled all of this, he believed he’d be able to swiftly begin an irreversible insurrection.

In the summer months leading up to the raid, John Brown stationed himself, his men, and a few members of his family in Washington County, Maryland, just across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry. He rented the Kennedy Farmhouse where they began to gather arms–mostly guns and pikes, which were easy to make and arm men with. He and his men would spend their days reading, strategizing, looking at maps, and playing checkers. They would only leave the farmhouse at night to avoid being seen by others who might be suspicious of Brown. His army numbered twenty-one: sixteen of the men were white, five of them black.

The Raid

In the late hours of October 16th, 1859, John Brown and his men began their raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He left three of his men behind as guards and advanced with the other eighteen towards the town. He anticipated hundreds or even thousands of freed slaves would join his mission while he was in Harpers Ferry.

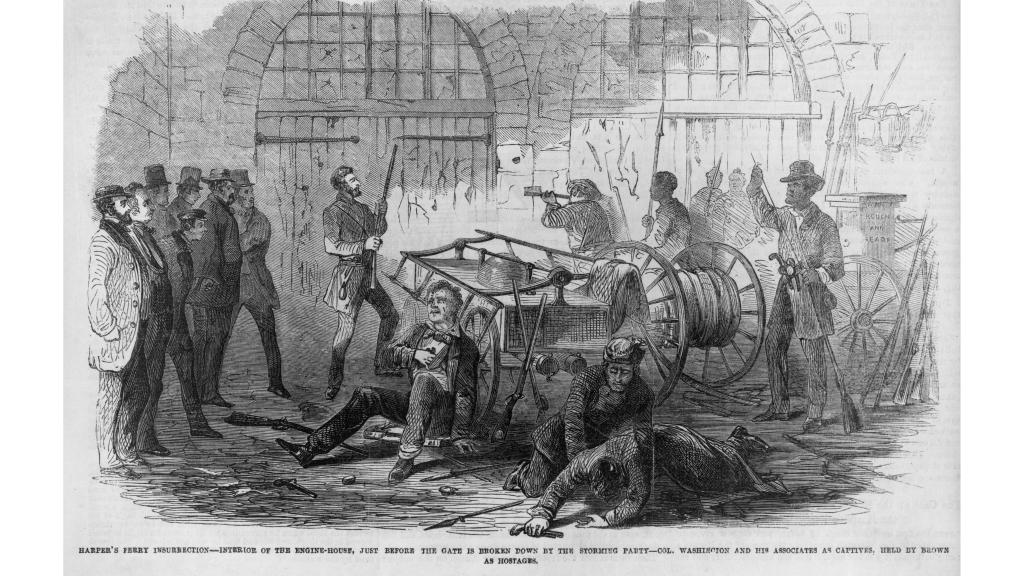

Under Brown’s instructions, a small group of raiders went to capture Lewis Washington (direct descendant of George Washington), free his slaves, and take some paraphernalia belonging to George Washington that Brown believed would be Talismans involved in their mission. The group left through the Allstadt House, where they freed more slaves and captured slave owner John Allstadt. They successfully returned to the rest of the party with Allstadt and Washington as hostages.

Meanwhile, Brown and the others had captured the Arsenal and Armory and taken both the Shenandoah and Potomac bridges. They also managed to cut telegraph lines to prevent communication from in and out of Harpers Ferry. The first night of the raid was considered a success, and the second day of the insurrection began.

The first casualty of the raid was a freed African American man that worked as a baggage handler at the Harpers Ferry train station. Heyward Shepherd was shot in the back and killed on the bridge when he encountered the raiders and refused to listen to them. He did not know anything about the raid that was happening–he had only ventured out to investigate why the early morning train was delayed, and had believed the men to be robbers. Another local heard the shot that killed Shepherd and sounded the alarm that would bring in the militias from the rest of Jefferson County.

Shepherd later became a symbol for the Lost Cause and other pro-Confederacy ideologies during the Civil War, being a black man who was killed during a raid that was meant to help African Americans.

In the early hours of October 17th, a train passed through Harpers Ferry and was stopped for several hours. Brown did nothing to harm the passengers and even talked with them while they were detained. As the train carried on, news spread of the slave rebellion and raid (albeit slowly, with no working telegraph wires) and U.S. federal troops were notified.

As more armory employees arrived for work in the morning, they were also taken as hostages and ordered to work. An estimated sixty to seventy hostages were held in the buildings included in the armory, although there’s no official record of the amount.

Local militias from neighboring towns–including Charles Town, Shepherdstown, Martinsburg, and more–arrived in the late morning, and started shooting at Brown’s men outside the armory. He was quickly surrounded, and had no means of escape–he had hardly any freed slaves joining his raid, and was now trapped in Harpers Ferry. The bridges they’d captured had been lost. Their only means of escape were to swim across the fast moving, large Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers–an impossible feat.

Brown and his men were in one of the engine houses in the armory, which would be known as John Brown’s Fort. There were many shots fired and deaths in the afternoon of October 17th, including the deaths of two of John Brown’s sons–one of whom was carrying a flag of surrender to the townspeople.

The townspeople and militiamen freed many of the hostages and kept Brown and his remaining stuck inside the engine house. Some of his remaining men managed to escape and many others were shot and killed in their attempts.

By nightfall, Robert E. Lee and nearly a hundred marines arrived in Harpers Ferry. The marines and Lee broke down the engine house’s doors the next morning, Oct. 18th, after Brown refused to surrender. Fighting ensued, and several more people were killed or injured, including Brown. He and his remaining men surrendered and were taken to Charles Town to be jailed and tried.

The Aftermath

John Brown was charged with murder, conspiring with enslaved people to rebel, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. His other captured raiders were charged with the same or similar acts. They were found guilty of all charges–it only took forty-five minutes for jurors to agree on a decision for Brown. He was sentenced to hanging on November 2nd, 1859.

Brown was executed on December 2nd, 1859, in the fields of Charles Town, Virginia. The crowd was massive, and several important and famous people were among the onlookers–including John Wilkes Booth, future Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, and poet Walt Whitman. Bystanders said Brown was fearless as he faced his death on the gallows. After his death, Brown was buried in North Elba, New York. His fellow captured raiders faced the same fate, yet the few that escaped after the raid evaded their deaths.

The land in which he was hanged would be later owned by John Thomas Gibson, who was the first commander of the first Charles Town militia that would respond to John Brown’s raid. Gibson built his home (the Gibson-Todd House) overtop of the spot where Brown was executed, purposefully placing the cornerstone for the house on the exact location Brown died.

The Impact

Although John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry failed and only killed sixteen people (ten of them being Brown’s own men), the rebellion served as a catalyst for the Civil War. Any relations between the North and South were truly destroyed. It intensified the debate on slavery, further driving the wedge between the two regions of the United States.

Also, Appalachia was a significant battleground for the Civil War–the mountainous terrain was a strategic location for both the Union and the Confederacy to have, and would later lay the road for West Virginia’s secession into the Union. Many Virginians had opposing feelings about slavery and their position in the war.

There were more Confederate sympathies in the Southern parts of Virginia than the Northern parts, creating tension between communities, which highlighted the diverse political opinion between Appalachians during this time–ones that still exist even now. After a while, the Northwestern parts of Virginia’s political differences lead to a complete succession into the Union, and West Virginia was created in 1863. Jefferson county, where the raid took place, went with it. Without John Brown, the great state of West Virginia might not exist—at the very least, not without all its parts.

John Brown’s dedication to his mission–even if not every Appalachian agreed with his thoughts and actions at the time–resonated with many. Appalachia is a region filled with individuals fiercely dedicated to their beliefs and ideals. Brown’s drastic action and willingness to give his own life for his cause struck a chord with many Appalachians, where independence and defiance to outside influences has long been established.

Brown’s actions are a source of inspiration for many Appalachians involved in matters of social justice and resistance to injustice. Dedication to fairness, equity, and fighting for what we believe in is what makes Appalachia what it is today. Although Brown’s mission failed, we can still admire his drive to fight for what he believed in and what is right–the true Appalachian way.