This article was written by a resident of Lansing, North Carolina. Learn about the community’s ongoing effort to recover from Hurricane Helene at lansingbtr.org, and please consider donating to support local recovery efforts here.

Authored by Anna Wheeler, Grants and Data Manager, Virginia Harm Reduction Coalition

January 22, 2025

Lansing is a rural town in the Blue Ridge Mountains, tucked in the northwestern corner of North Carolina. Many would call it an anachronism––a place out of sync with time. The old Virginia Creeper train used to run right through the heart of it, and older folks say more happened in the town then. To the naked eye, not much happens here now.

It’s only fifteen minutes from better-known West Jefferson, but as West Jefferson has transformed over the past few decades to meet the demands of ecotourism, Lansing has only pawed at the idea of becoming something different. The fixtures of the town are a small, family-run grocery store, a tiny post office, a beloved pizza spot, and just a handful of other local businesses. No bank, no Dollar General, no liquor licenses. From time to time a new little concept will pop up––a novel music venue or a butcher shop––but these don’t last long. At first there was a stop sign at the town’s one and only intersection, where highway 194 from Virginia runs along Helton Creek and into the main street. Years ago, the town council decided to put up a traffic light at that intersection. It was more of a nuisance than a bright idea. Eventually they took it down and put the stop sign back.

Past that stop sign, the highway curves along Big Horse Creek for about a mile before coming to a gas station that’s been owned by the same immigrant family for decades. The pumps are practically antiques and you have to pay inside. Across from it, a bridge turns left onto Little Horse Creek Road. My dad lives about seven miles out that road, and I’ve been driving it since I was fourteen. After I turn onto that bridge, I don’t know whether I’m in the 20th or 21st century. Almost nothing has changed out there since 1998. Sure, there are a few more houses. Some developers have come in and cleared a few spots. There’s a little lavender farm there now that we all felt was an acceptable addition. But for the most part, the road from the bridge by the gas station to my dad’s house seven miles up is just like it always was. Thickets of blackberries pop up every summer at that same spot in the curve. The old uninhabited farm houses, pastoral testaments to a sad, complicated history, sit in exactly the same degree of disrepair. The forests and the hillsides have not shifted. Even the cows look to be the same cows they have always been. It is a place of defiant changelessness. If you venture too far off the pavement, you might end up in a backyard that’ll get you shot at. Many of the poor residents who live here are the descendants of people who stole this land from the Cherokee, the Creek, and the Shawnee. Kenny still grows tomatoes and makes moonshine up on the mountain. The meth house has caught on fire but hasn’t burned all the way down. It is both a kind and an unkind place. History has been unkind to it, to almost everyone who’s ever lived here. Some of the people have turned hard to survive, but the land has stayed soft.

Growing up, my siblings and I knew that we could borrow butter from Effie at the bottom of the hill, but if we went too far up into the holler in the opposite direction, we might get mistaken for a deer. My dad used to drive his truck up there to drop off boxes of food from the one local pantry to the family with five kids, three mean dogs, and no electricity. The spirit of giving was tenuous––some would take the help but make sure you saw the shotgun. Some would give the help but not take it. That impoverished Appalachian pride, handed down through generations, was hard to cut through.

Then there was a hurricane. Only a few folks were still around to remember the flood of 1940 that brought similar destruction. That was supposed to be a 500-year event. Nobody expected that a hurricane would touch these mountains like that again.

Including myself. The morning of the storm, I set out from my partner’s house to get back to my dad, who was recovering from a spinal injury and a wound infection. I woke up to the sound of trees cracking and realized the power was out. I didn’t want him to be home alone, so I left in the downpour. I didn’t make it much more than a mile before driving into an overflowing river and nearly being swept away by it. The road was flooded on one end and shattered on the other. By the next afternoon, when the water had receded enough for us to get out in my partner’s car (mine had drowned), we realized that what had happened on our road––every power line down, every private bridge crossing collapsed, the asphalt broken by landslides, houses half sunk, thousands of trees felled in a pattern suggestive of multiple tornados––had happened everywhere from here to the Tennessee state line and beyond.

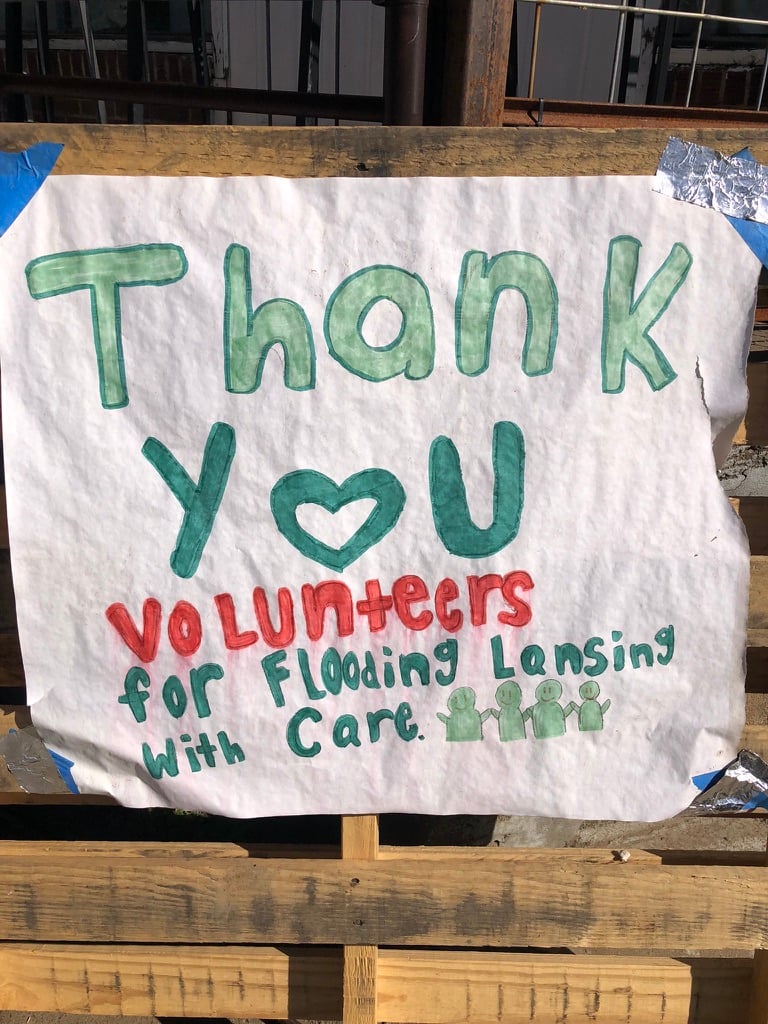

We also realized that we must be inaccessible to outside help, because there were no out-of-town emergency response personnel on the ground, and there would not be for weeks. Instead, every local we knew and every local we didn’t was out. Out in the road with their chainsaws chopping up massive trees that were blocking crucial routes. Out in the town carrying buckets of muddy flood water from buildings. Out on side-by-sides with boards and nails, creating temporary crossings for folks stranded on the wrong side of the creek. Local electricians––off duty––were out on four-wheelers cutting the live wires in the road. The family-owned grocery store, the post office, and the beloved pizza spot were gone. On the sidewalks in front of them were their guts, and locals organizing piles of the guts, sorting through what could be salvaged. All the shops on that street were washed out except one, spared by a few feet of elevation. It was a simple sandwich shop and small bar, a relatively new business in town. Everyone out volunteering, which meant just about everyone, got to drink for free at the end of the day. Overnight, a distribution center began operating out of that short-lived music venue which, before that, was a mechanic’s garage. In the coming months it would be overflowing with donated diapers and bleach from all over the southeast and beyond. But we started with bottled water, peanut butter, and propane tanks donated by whoever had them, strapped them to side by sides, and set out to find people stranded in the hollers without electricity or cell service. My dad was one of them. People who hadn’t lost much emptied their pantries to donate, and people who had lost everything came to see how they could help. My friend Lora brought out her grill and set it up in the middle of the road. She was dying of cancer––we lost her several months later––but she grilled all day every day for as long as hungry people kept showing up.

A group of my friends went scouting and found so many people stranded that they quickly threw together a team to map out the damage, rebuild collapsed bridges, and dispatch emergency food, water, and medicine. One of them was the owner of the sandwich shop where everyone could drink for free. Another was Lora. This group became a nonprofit called Lansing’s Bridge to Recovery, which I got to be a part of. We ended up rebuilding over a hundred bridges and roads damaged by the storm, and we are still rebuilding.

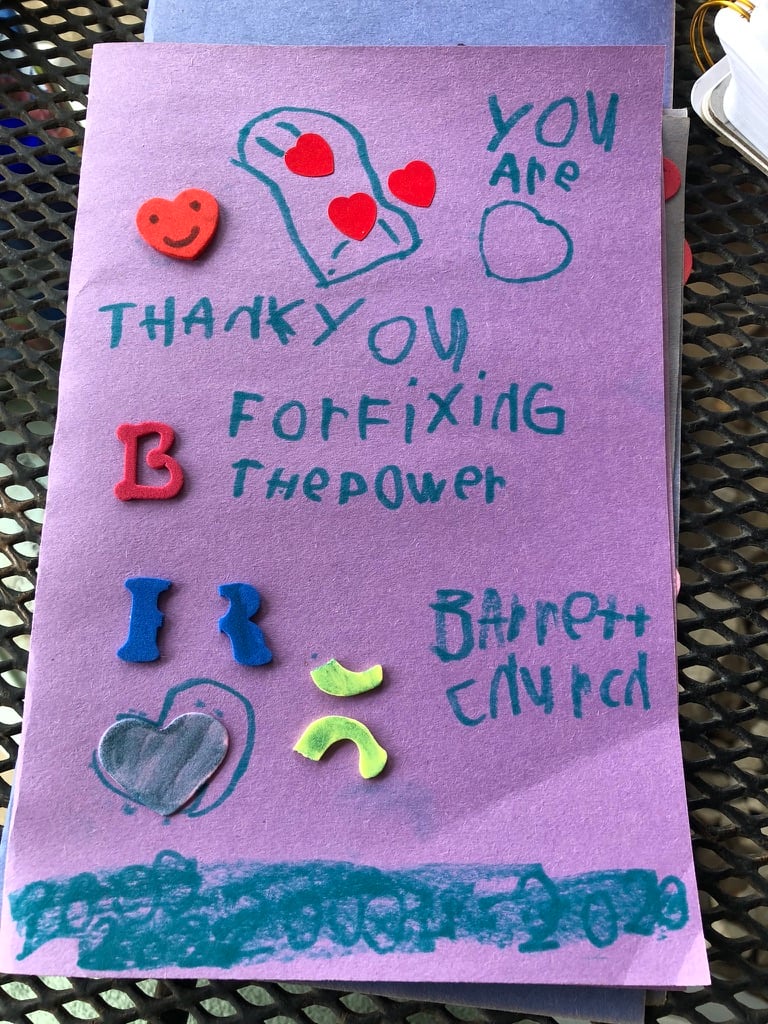

“You are ❤️ Thank you for fixing the power” – Barrett Church

The spirit of giving was suddenly much less tenuous. This “up by your bootstraps” and “the strongest survive” town was practicing real, meaningful community––what I have come to call communal self-care. Perhaps we had been shocked into it. I prefer to believe that the spirit was in us all along. When the distribution centers continued to operate as free grocery stores for months, nobody whispered derogatorily under their breath about who deserved what. When the Lutherans, Methodists, and Mennonites got together to start repairing houses, the subject of denominational differences didn’t come up. When the folks from the hollers who didn’t believe in “taking handouts” came down asking for tents and sleeping bags, I knew that this disaster had changed at least one thing here for the better. It had opened hearts.This community was loving itself back to health, one meal and blanket and bridge at a time.

I would have called Lansing resilient before, but with a different connotation. I would have said this town would survive a crisis because it was hardened and the people were fiercely self-reliant. But that is not really resilience. Resilience is, in a big way, the art of allowing yourself to be helped. Lansing understood immediately that we all had to help each other, and we all had to let ourselves be helped back. People gave and received as they were able, and there was no shame in it. There is no room for shame in resiliency.

The drive up Little Horse Creek Road is different now. The blackberries didn’t come back in that curve this Spring, probably because of the landslides. The hills have shifted and much of the forest is laying flat. Not all of the livestock survived. Not all of the people did either. Every time it rains now I remember them. And all the bridges were destroyed, so now all the bridges are new. That’s got to be a metaphor for something more, I think.

At seven in the morning about a week after the storm hit––and about a week still before the power would finally come back on––Kenny who makes moonshine on the mountain knocked on the door of my dad’s house. He’s never had a car, so he’d hiked three miles to let us know there was a deer in his bathtub for us. He’d shot and cleaned it at five o’clock that same morning. I took the four-wheel drive up to get it. Kenny and I heaved it into a contractor bag, bloody and sopping. We portioned it up on my dad’s front porch and cooked it for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. All the other meat in the freezer had spoiled, so this was a feast. Little acts of love are resilience. Imagine a community built on a million little acts of love.